The corset is perhaps the most controversial garment in the history of fashion. It is part of history and was in fashion for over 400 years. As a symbol it has served well in the minds of Western culture. As “instruments of torture/oppression”, a clear announcement of wealth, and a demonstration of a women’s femininity. Ivan Sayers of Vancouver, museum consultant and clothing historian, explains the attraction of corsets as “beauty by impairment”. The more a woman was impaired by her clothing and appearance in earlier times, the greater was her influence. In fact, it was her duty to be uncomfortable, if necessary, because on her shoulders rode the entire social position of the family. Meanwhile, the servant doing the work in the back kitchen had her own version of a corset. It was a bodice that laced up the front and was worn over the dress - and that established her lack of status. A woman with status had servants to help her into her corset, which laced up the back - an important distinction.

Drawing from 1893.

For the origin of the corset we must travel back into far antiquity. The origins of the embryo corset or boned bodice is unknown but it would have started from the hunter who realized that by binding his torso stiffly with sharpened bone or fire-hardened stick would give support during the fatigues of a chase. At the dawn of civilization there are distinct evidences of the use of contrivances for the reduction and formation of the female figure. The ruins of Polenqui, South America, brought to light evidence of the existence of a complicated and elaborate waist-bondage, which by a system of circular and transverse folding and looping, confines the waist from just below the ribs to the hips as firmly and compactly as Victorian corsets.

Women had begun to establish themselves as professional staymakers in the eighteenth century. By the early nineteenth century, the majority of small and medium-sized corset manufacturers and retailers were women. A few names, such as Madame Saint-Evron, who had a workshop on the rue de Richelieu in the 1820s where she made and sold a variety of corsets, including corsets without busks, corsets for pregnant women, French corsets, English corsets, and night corsets. At the 1823 exposition in Paris, Madame Mayer presented corsets made without a busk or whalebone, which utilised cording. Corsets were produced in great numbers and in all price ranges. In 1855, some 10,000 workers in Paris specialized in the production of corsets. In 1861 it was estimated that the number of corsets sold annually in Paris was 1.2 million. The cheapest corsets for workers and peasants cost from 3 to 20 francs each; by comparison, silk corsets cost from 25 to 60 francs, and some corsets decorated with handmade lace sold for 200 francs. The French were famous for custom-made corsets in luxury materials. The English and American markets were dominated by mass-produced corsets made in a variety of styles and standardized sizes - usually 18 to 30 inches at the waist. Corset design continued to develop in response to technological inventions and changes in fashion. Edwin Izod invented the steam moulding process in 1868: this involved first the creation of “ideal” torso forms, which were cast, usually in metal. Then corsets were placed over the metal forms which were heated until the corsets took on the correct shape.

Advertisement from 1903.

In the 1500s, the busk was an important component of the corset. To ensure the wearer maintained an erect posture, a piece of wood, metal or bone was inserted in a slot down the center front of the corset where it was tied with ribbons and decorated with amorous images. It was, at that time suggested that a hard busk and tight stays might cause miscarriages. Court society imposed its aesthetic of erectness, which was also a way of mastering the passions and emphasizing the defenses indispensable to a female nature seen as “fragile”. However, as early as 1588, French essayist Michel de Montaigne described how the famous surgeon “Ambroise Paré had seen on the dissection table these pretty women with slender waists, lifted the skin and the flesh, and showed us their ribs which overlapped each other”. The corset has been blamed for causing dozens of diseases, from cancer to curvature of the spine, deformities of the ribs and displacements of the internal organs, respiratory and circulatory diseases, birth defects, miscarriages, and “female complaints”, as well as medical traumas such as broken ribs and puncture wounds.

Alexander McQueen A/W 09-10

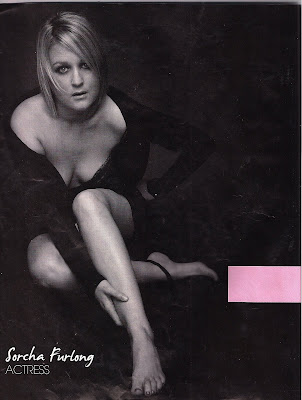

Today corsets and boned bodices are still evident within fashion and more so in couture, bridal-wear and lingerie. However, designers still buy into the benefits of corsets body-extension and body-addition and as a means of simultaneously concealing and revealing. Bridal designers such as Vera Wang and Reem Acra create confectionary pieces that slim the waist, enhance the bustline and hips for womens ‘big day’. Vivienne Westwood, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Alexander Mc Queen, Hussein Chalayan and Lacroix make historical and nostalgic references with modern corsetary and boned dresses. However, the sexual attitudes and behaviour has become dramically freer compared to the 19th century as the visible corset has become a socially acceptable form of erotic display.